2021/2022

In The Shadow of False Light

Nobel Peace Prize Commission

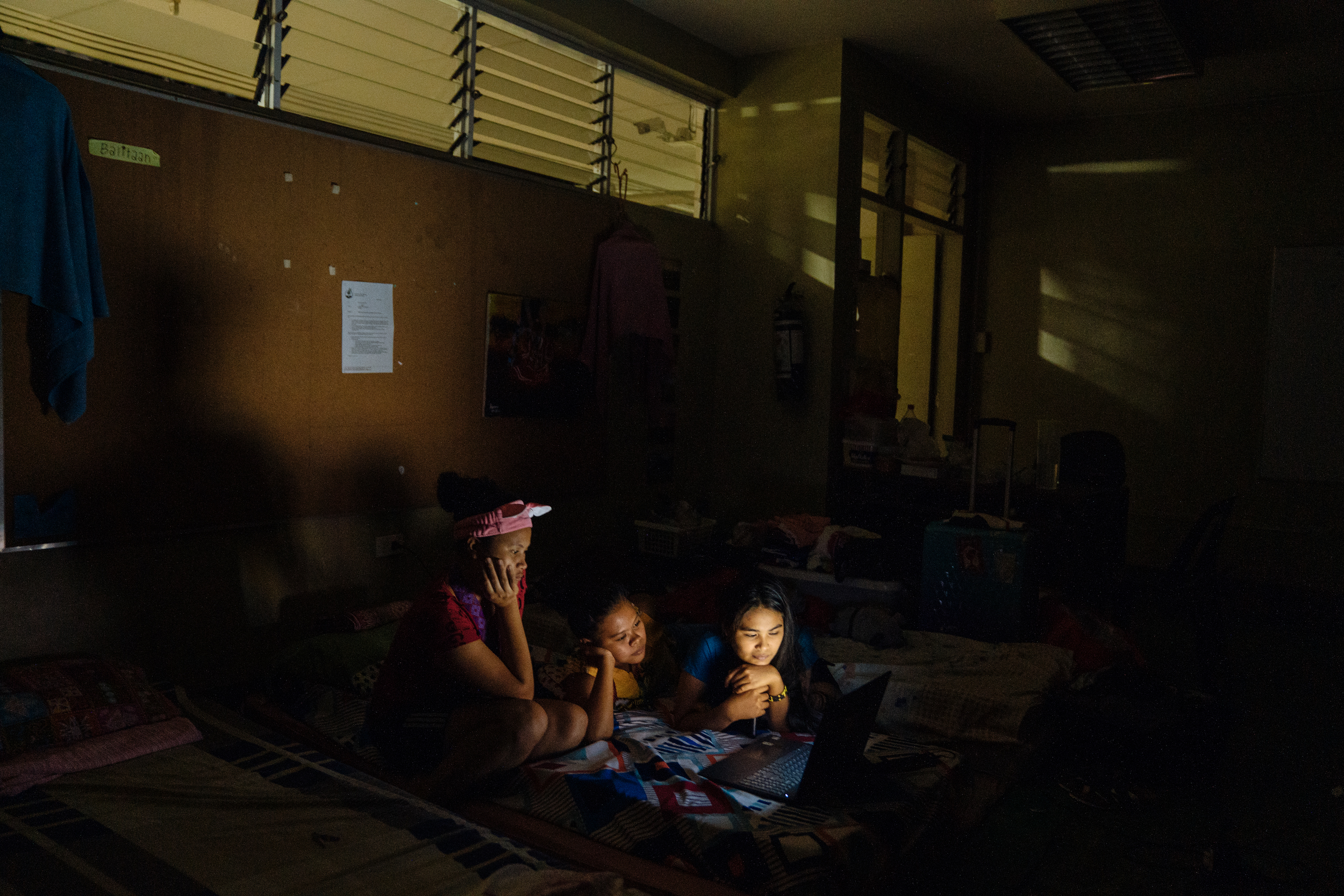

A child in a Manila shanty inserts a one peso coin into a vending machine, for five minutes of wifi. A TikTok content moderator works from home, scrolling through thousands of posts for violations. His family catches glimpses of the pornography, murder videos, and hate speech he needs to report. A digital creative living paycheck to paycheck accepts a gig as a troll, becoming part of a disinformation operation run by a politician. A fact checker gathers information to disprove falsehoods going viral on Facebook. She devotes as much as two weeks to research a post that took seconds to manufacture and share.

Light can obscure as much as it illuminates. In the Philippine landscape, limited, uneven Internet access creates scattered and isolated islands of sense-making, which fail to connect into a cohesive image.

Here, disorder is as ordinary as a kid with a toy gun, pretending he is a hitman killing a drug user in a neighborhood ravaged by President Duterte’s drug war. When Facebook is free for all, but less than a third of Filipino children have Internet access for their online classes, how is the emergence of disinformation surprising?

Unlike China’s centralised army of trolls, in our country disinformation is a thriving, diverse ecosystem of competing, clashing operations, powered by digital and creative laborers from all levels of expertise, especially educated, working-class Filipinos hungry for a better life. Scarcity has made them pragmatic: Disinformation isn’t propaganda; it’s just another PR campaign.. Whatever moral discomfort they feel, buys them and their families a little more security., and anyway their personal accountability is abstracted by the flickering shadows of a professionalised system. Information disorder won Duterte the presidency in 2016, and has since evolved into a legitimate service bought by clients spanning the political spectrum, a matter of course, not concern.

Light can obscure as much as it illuminates. In the Philippine landscape, limited, uneven Internet access creates scattered and isolated islands of sense-making, which fail to connect into a cohesive image.

Here, disorder is as ordinary as a kid with a toy gun, pretending he is a hitman killing a drug user in a neighborhood ravaged by President Duterte’s drug war. When Facebook is free for all, but less than a third of Filipino children have Internet access for their online classes, how is the emergence of disinformation surprising?

Unlike China’s centralised army of trolls, in our country disinformation is a thriving, diverse ecosystem of competing, clashing operations, powered by digital and creative laborers from all levels of expertise, especially educated, working-class Filipinos hungry for a better life. Scarcity has made them pragmatic: Disinformation isn’t propaganda; it’s just another PR campaign.. Whatever moral discomfort they feel, buys them and their families a little more security., and anyway their personal accountability is abstracted by the flickering shadows of a professionalised system. Information disorder won Duterte the presidency in 2016, and has since evolved into a legitimate service bought by clients spanning the political spectrum, a matter of course, not concern.

Manila, still in the claws of light. The narratives being spun are growing even more hopelessly tangled. The signal is scrambled, the light blue, now, green, now, red, and the picture pixelates, duplicates, disconnects. The stillness of our bodies is not stoicism, but shock, born of endless cycles of despair and belief. Blankly, we look to one source of truth and then another, no longer sure what we are looking for. A half-had dream? The promise of the West? An old-fashioned belief? Democracy?

Maria Ressa calls upon each of us to hold the line. In order to do so, we must draw it, again and again, around ourselves, around our community, around the things we can’t afford to lose.

When Rappler reporter Rambo Talabong was doxxed by Mocha Uson, Duterte’s troll-in-chief at the time, it was the first time that the threat of disinformation became real to him. But it was also the first time he experienced true solidarity. “I felt that there was a community waiting for me… It crystallised my belief in why we have to do this.”

- Nicola Sebastian, Text for Nobel Peace Center Exhibition

Maria Ressa calls upon each of us to hold the line. In order to do so, we must draw it, again and again, around ourselves, around our community, around the things we can’t afford to lose.

When Rappler reporter Rambo Talabong was doxxed by Mocha Uson, Duterte’s troll-in-chief at the time, it was the first time that the threat of disinformation became real to him. But it was also the first time he experienced true solidarity. “I felt that there was a community waiting for me… It crystallised my belief in why we have to do this.”

- Nicola Sebastian, Text for Nobel Peace Center Exhibition

This project was funded by the Nobel Peace Center, in response to Maria Ressa’s work, and was exhibited in the Nobel Peace Center for a year.

It was later on published in National Geographic Magazine, and won an award in the Pictures of the Year International in 2022.

hannahrey.ph (at) gmail.com